Here is a recent interview on Artribune, talking with Alessia Tommasini (2020, march 24).

The text is in italian therefore just below in the blog here you can find the English version. I apologize in advance for any errors in the translation.

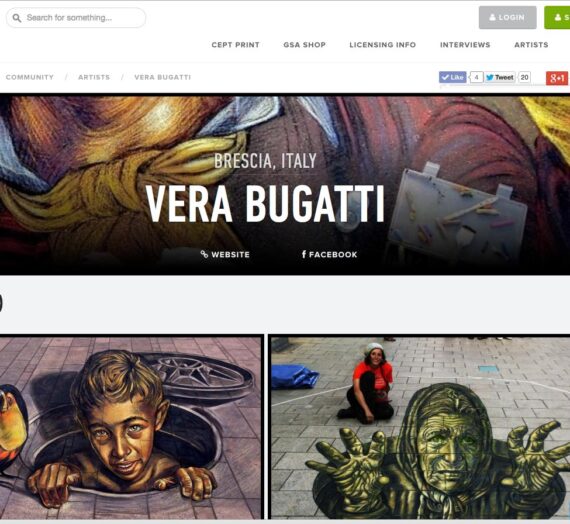

Anamorphic street painting expert, Vera Bugatti is divided between street painting and the activity of librarian and here she reflects on the sense of Street Art.

Born in Brescia in 1979, Vera graduated in History of Art in Parma, worked as a researcher and and library field.

Her works are featured in Julie Kirk’s Sidewalk Canvas, London 2011; Street art by Russ Thorne, London 2014; The Art of Chalk by Tracy Lee Stum, USA 2016; Street Art en Europe by Nath Oxygène and Brigitte Silhol, Paris 2018; Designing graphic illusions, China 2019.

Active since 2008 and anamorphic street painting expert since 2015, she has painted in Italy, Holland, France, Germany, Ireland, Croatia, Austria, Malta, Sweden, Denmark, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Portugal, Spain, Latvia, Russia, Great Britain, Bulgaria, Belgium, the United States, Mexico, the United Arab Emirates and India.

Can you tell us about your latest job?

I’ll tell you about DE(ath)HORNING, painted in Bromolla, Sweden, at the Ifo Center Outdoor Gallery, and dedicated to the topic of surgical rhinoceros dehorning. One of the strategies (short-term solution but now widely used) to protect these beautiful ungulates from poaching is the periodic removal of the horn, which on the black market can yield up to 95 thousand dollars/kg. The demand comes from the countries of Southeast Asia, in particular from China, where the pulverized horn is considered a miraculous ingredient for traditional preparations intended for medical treatment or is considered an aphrodisiac. All five species of rhinos in the world are highly endangered and the practice of dehorning has allowed the defense of hundreds of specimens. Despite this, only the idea of amputation as a salvific method evokes a sense of brutality. We insist on dabbing, with our methods, where we have already irreparably damaged the environment and animals.

What did you want to communicate with your work?

In the painting, the rhino on the right, dying, questions us. On the left a strange winged rhinoceros (a kind of chimera. How can we think of a rhino without a horn?) Hovers in the void but is held on the ground by a strange pinkish rope/chain that comes from the medicinal collar and ends in a heavy and rigid object that looks like a balloon. The sky is absent, it has changed into an octane-colored tangle that takes your breath away.

In the center, a woman no longer young, hissing with a haughty look, shows a knife. She can decide whether to amputate other horns or cut the rope that makes the flying rhino prisoner. The title of the work, through a play on words, refers to death. There is no peaceful solution to a Gordian knot.

If you had to tell your technique and your style, what would you say?

I’m not really able to define myself on a stylistic level. When asked, I show some pictures and say: “you can decide”. Figurative, okay, but there are those who describe it as surreal, dreamlike, those who bring it closer to magical Realism, those who approach the sacred, pantheism, those who perceive its melancholy streak, those who find every disturbing and disturbing piece of mine. I like to think that it can be a reflection of all these things at the same time.

There seems to be a common thread that unites your works, can you tell us about it?

A red thread binds human disturbances in my pieces to social issues and the livability (unlivability) of the planet. Melancholy and hope also. I trace restless elegies of time.

I focus on the individual and the components of an fragmented identity. The result is alienating works, with a deliberately incorrect spatiality. This poetics, declined in different areas, can be found throughout my artistic production: from the bas-reliefs in wire and nails to the new worlds enclosed by my optical boxes up to the stories told through the electric motor anamorphoses of the Theaters of Memory, a small tribute to the world of pre-cinema. I realize that I cannot forcefully reach the social criticism that I would like to express. I think I’m still too cumbersome within my works. In those boxes, in those sectioned walls, in those wrinkled faces that interrogate, in those desperate children who cry, in animals, in teratologies, there is always me.

What does Street Art mean to you?

A complex polyhedron that any attempt to circumscribe lacks important and unedited aspects. More than a single definition, a distinction between Street Art, Urban Art, graffiti, writing, urban art would be necessary.

If we talk about unauthorized public art, the field narrows, but in my opinion the recent dynamism that is affecting the phenomenon makes it even more heterogeneous and distant from the first social graffiti. Street Art runs the risk of no longer representing a counterculture, short-circuits with the variegated and uncontrollable cauldron of social media, it is often sold as urban redevelopment and without due attention to the message contained in the works. Much has changed therefore, and my story begins in retrospect but, above all, without the aforementioned pregnant background. In this sense, I am an outsider. For this reason, I refer to my pieces with the term of urban art and I would like even more to talk about it as contemporary art (isn’t this after all?).

Why did you approach Street Art?

Few illegal pieces (among other things in recent years) do not make me a street artist. So, let’s talk about urban art, muralism, street painting, narcissism, ordinary madness, whatever you prefer. I didn’t start painting on the street doing writing in the nineties, like many artists I know. At that time, I drew little (and only for myself) and wrote a lot. Then I enrolled in Letters and I was thinking of a future as a researcher in the context of modern history, an aspiring allologist with her head in the clouds.

Today my house is full of books and I have been a librarian for fourteen years. Even books, like art, are worlds of infinite thickness. The first taste of the ‘road’ went through Madonnara art, I was really fascinated by its ephemeral vocation. It was the summer of 2003 and I was preparing my degree thesis on heresy and figurative arts in the 16th century, another great passion.

An adult vocation, one might say. My first drawing on asphalt was a copy of Giuditta and Oloferne di Caravaggio. Each gust of wind was worth a handful of color removed and one of added dust, the rain became a scourge, the fingers hurt. I was hesitant, I was welcomed by special people and I lived unforgettable experiences around Europe for a few years. The immediate need to create personal and communicating subjects (how heavy I am, I know, with this history of meaning) then led me to experiment and the pieces became complex and stretched up to what was needed to see them emerge from the ground and even more to the point of not being ‘photographable’.

Friends affectionately called them 2Dpoint7. Not true three-dimensional illusions therefore, but something that we wanted to get closer and closer.

So, I started with real anamorphic street painting and continue to dedicate myself to it today. I see it as a tool capable of giving greater impact to the message of my works.

How do you think it is perceived by people?

I often wonder what others perceive. If they catch the quotes inside the pieces, if they read the texts (they are verbose, of course) that describe them, if they understand the word games of the titles. The fact that they simply ask questions, that they disagree, that something is moving, already satisfies me. I don’t demand too much attention, I’m a grain of sand in the desert. But if that grain together with others draws ways, then it has an end.

The creation of a work of art, in a world of alibi, is an ethical responsibility. It should stand out from the visual noise in which we are immersed.

Now what would you like to explore? What would you like to paint and interpret?

In recent years I have oriented myself on large walls, also driven by the desire to create something that could last over time, after at least fifteen years of ephemeral works. Maybe out of a long-term memory craving. I often speak of transience in my works. Now I perceive it deeply, also through my dream activity (my creative chest). 2019 was a terrible year for my health. I didn’t want to paint anymore. Stuck in relation to big projects, I wanted to create something intimate and cathartic. So, I designed monochrome pieces dedicated to abandoned places, especially a large building that I had found so suggestive that my brain (I could even say heart) was dazed. Works dedicated to mental health but basically autobiographical, a little therapy for myself.