Nel mese di marzo, quando tutto sembrava nuovamente piombato nell’immobilismo da pandemia, mentre vedevo i progetti scalare ancora e accoglievo stancamente l’incertezza come condizione abituale, mi sono rifugiata in una bolla creativa.

Un piccolo progetto nella mia città, Brescia, e l’attesa fiduciosa di un amico che aveva creduto in me sfidando la sorte in un momento nel quale pensare all’apertura di una nuova attività pareva indubbiamente follia. Mi aveva chiamata in autunno, ancora titubante ma entusiasta, e si preparava ora ad ospitarmi segretamente in un luogo magico del centro storico.

Parlo di Iyas Ashkar, palestinese mio coetaneo che vive e lavora da vent’anni a Brescia nell’ambito della ristorazione (chi fra i bresciani non ha conosciuto I Nazareni?).

Si definisce “un arabo, un italiano, un migrante, un viaggiatore: un’isola” e per questo non è un solo un esperto di cucina ma anche un promotore di intercultura e un uomo impegnato nel sociale per la città (con il progetto Cibo per tutti Carmine).

Gli avevo detto che non avrei accettato commissioni se non a soggetto libero. Lui desiderava da tempo coinvolgermi e mi ha raccontato la storia di Handala, il bambino creato nel 1969 dall’artista Naji Al Ali e divenuto poi un’icona della Palestina a livello internazionale. Ricordavo di aver notato la presenza di questo personaggio all’interno di opere di street art e ne conoscevo il significato ma non ne avevo mai veramente approfondito il contesto.

Handala, apparso per la prima volta sul quotidiano kuwaitiano Al Siyyasa (“La politica”), ha l’aspetto di un bambino di dieci anni dai capelli irsuti, coi vestiti rattoppati e i piedi nudi. Volta le spalle al mondo in segno di rifiuto, una figura muta ma ostinata il cui nome deriva da “al-hanzal”, arbusto spinoso mediorentale dai frutti amari. Il suo sguardo è rivolto alla tragedia palestinese, alla sua gente che ancora resiste nonostante tutto.

In parte è considerato un riflesso del suo stesso creatore, che a 10 anni fu costretto ad emigrare in un campo profughi a sud del Libano, a seguito della proclamazione dello stato di Israele. L’artista Naji è purtroppo stato ucciso ma la sua memoria resta viva in proprio Handala, il bambino che potrà iniziare a crescere solo quando potrà tornare nella sua terra.

Iyas sapeva che quel racconto mi avrebbe suggestionata ma mi ha chiesto di fare di più, di immaginare un lieto fine per questa storia. Mi sembrava utopia, tanto più col mio stile poco incline ai dolci epiloghi e considerato che i personaggi che creo difficilmente regalano un sorriso.

La questione palestinese restava un macigno e non ne uscivo assolutamente con un pensiero di speranza, più di centomila morti in settant’anni e un dramma insuperabile. Eppure gli ho detto che quella sfida mi piaceva, di non pretendere una scena edulcorata ma di lasciarmi fare. Desideravo che chi avrebbe guardato la mia opera si sentisse trafitto ma al contempo conquistato.

Così è nato il pezzo “Handala è tornato a casa”, pensato per la realtà che aprirà a brevissimo col nome di DUKKA (Non solo Hummus) in Via Musei 9/B, in pieno centro storico, accanto alla chiesa di S. Faustino in Riposo. (Dukka, o Za’tar, è un insieme di erbe che con il sesamo tostato e il sale creano una miscela usata in molte ricette palestinesi, è il profumo della terra di Iyas e per questo vi invito a leggere il suo blog nonsolohummus.it).

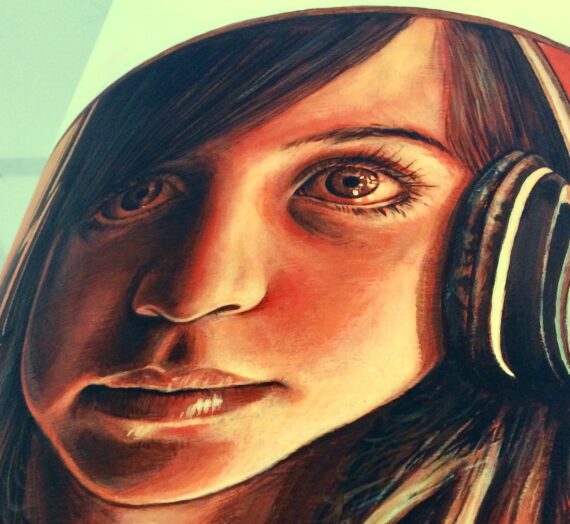

Ora vi racconto la mia opera. La scena è incorniciata da un arco. Handala è appena arrivato e la sua valigia ammaccata campeggia davanti a noi, è rossa e mostra un adesivo bianco che rappresenta il vero disegno di Naji. Il bambino è ormai divenuto un ragazzo dallo sguardo deciso e indossa un cappello che disciplina la sua capigliatura. In una mano tiene una kefiah sgualcita e con l’altra regge una cordicella poco visibile che è collegata ad una chiave appesa al muro, anch’essa un po’ in secondo piano.

La chiave, vero simbolo del diritto al ritorno, è legata alla commemorazione della Nakba, la “catastrofe” dei palestinesi che rievoca l’esilio di 700 mila persone dalle loro case nel maggio del 1948. Un evento che viene celebrato in tutto il mondo dalle comunità della diaspora ma particolarmente in Cisgiordania, Gaza e Gerusalemme est.

Nella mia opera la chiave è appesa ad un chiodo ma Handala si tiene ancora in contatto con essa, un gesto di timore giustificato dai tanti anni di attesa. Sarà tutto vero? Meglio tenersi pronti.

Alla sua destra una donna anziana accenna un sorriso. Porta un abito decorato tradizionale e sulle sue mani nodose è appoggiato un uccello dal becco adunco, una nettarinia palestinese (dichiarata nel 2015 uccello nazionale), attributo che la fa apparire come una santa o una sibilla. Personificazione della Palestina, la figura femminile emana saggezza e forza scaturita dalle vicissitudini che ne hanno segnato volto e mani. Contemporaneamente accoglie il volatile con delicatezza, lasciando che anch’esso ci guardi.

So di aver dipinto un sogno dal sapore utopico ma nello sguardo di Handala c’è tutta la determinazione necessaria per metterci di fronte alle nostre responsabilità, dopo più di settantanni è davvero una questione mondiale. Anche se ci crediamo assolti, siamo tutti coinvolti.

(Now the text in English)

In March, when everything seemed once again plunged into pandemic immobility, while I saw the projects climb again and I tiredly accepted uncertainty as a usual condition, I took refuge in a creative bubble. A small project in my city, Brescia, and the confident expectation of a friend who had believed in me, challenging fate at a time when thinking about opening a new business undoubtedly seemed madness. He had called me in autumn, still hesitant but enthusiastic, and he was now preparing to host me secretly in a magical place in the historic city center.

I’m talking about Iyas Ashkar, a Palestinian of my age who has lived and worked for twenty years in Brescia in a restaurant. He defines himself as “an Arab, an Italian, a migrant, a traveler: an island” and for this reason he is not only a cooking expert but also a promoter of inter-culture and a man engaged in social work for the city.

I told him that I would not accept commissions except for a free subject. He really wanted to involve me and so he told me about the story of Handala, the child created in 1969 by the artist Naji Al Ali and who later became an icon of Palestine on an international level. I remembered having noticed the presence of this character in street art works and I knew its meaning but I had never really deepened its context.

Handala, which first appeared in the Kuwaiti newspaper Al Siyyasa (“Politics”), looks like a ten-year-old boy with shaggy hair, patched clothes and bare feet. He turns his back on the world as a sign of rejection, a mute but stubborn figure whose name derives from “al-hanzal”, a thorny Middle Eastern shrub with bitter fruits. His gaze is turned to the Palestinian tragedy, to its people, to the desperation of those who still resist despite everything. The shape of his head resembles a sun, which according to young Palestinians symbolizes future hope, his hair is similar to the quills of a hedgehog, to defend himself and he has bare feet because he is poor like the children of the refugee camps.

In part the character is considered a reflection of its own creator, who at 10 was forced to emigrate to a refugee camp in southern Lebanon following the proclamation of the state of Israel. Unfortunately, the artist Naji was killed but his memory remains alive in his Handala, the child who can only begin to grow when he can return to his homeland.

Iyas knew that such an incredible story would have influenced me but he asked me to do more, to imagine a happy ending for this story. It seemed utopia to me, all the more so with my style not very inclined to sweet epilogues and my characters that hardly give a smile. The Palestinian question remained a boulder and I absolutely did not come out with a thought of hope, more than a hundred thousand deaths in seventy years and an insurmountable drama. Yet I told him that I liked that challenge, not to expect a sweetened scene but to let me work on it.

I wanted those who looked at my work to feel pierced but at the same time conquered. In this way the piece “Handala is back home” was born, designed for the restaurant that will open very shortly with the name of DUKKA in the historic center.

Handala has just arrived and his battered suitcase stands out in front of us, it is red and shows a white sticker that represents Naji’s real drawing. The child is now a boy with a determined look, he wears a hat that disciplines his hair. In one hand he holds a crumpled keffiyeh and in the other he holds a barely visible cord that is connected to a key hanging on the wall, also a little in the background.

The key, a true symbol of the right of return, is linked to Nakba, the Palestinian “catastrophe” which commemorates the exile of 700,000 people from their homes in May 1948 with the birth of the Israeli state. An event that is celebrated all over the world by the communities of the diaspora but particularly in the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem.

In my work the key hangs on a nail but Handala still keeps in touch with it, a gesture of fear justified by the many years of waiting. Will it all be true? Better get ready.

To his right, an old woman smiles. She wears a traditionally decorated dress and on her gnarled hands rests a bird with a hooked beak, a Palestinian nectarine (declared a national bird in 2015), an attribute that makes her look like a saint or a sibyl. Personification of Palestine, the female figure emanates wisdom and strength despite the vicissitudes that have marked her face and hands, and at the same time welcomes the bird with delicacy, letting it look at us too.

I know I painted a dream with a utopian flavor but in Handala’s gaze there is all the determination necessary to face up to our responsibilities, after more than seventy years we can consider that situation truly a world issue. Even if we believe ourselves acquitted, we are all involved.