Qualche mese fa ho pubblicato la poetica dell’opera PAG, realizzata a Montichiari (BS) nel mese di luglio. Vi avevo chiesto pazienza per il resoconto del progetto e ve ne avrei domandata ancora, come mio solito, perché questa settimana avrei dovuto essere in azione creativa su una nuova parete.

Invece sono ko tecnico causa covid e dopo sette giorni ho praticamente ancora tutti i sintomi possibili (gli amici sanno che il mio sistema immunitario è sempre sul pezzo… ma mi riprenderò).

Ho quindi deciso di raccontarvi di Montichiari perché c’è ancora chi mi ferma e chiede, ma la polemica? Ci sarebbe molto da dire, ma forse poco che valga la pena davvero ricordare. In fondo a luglio non ho voluto rilasciare interviste, volevo parlasse l’opera, mi pareva la miglior risposta, e tale risposta resta lì a disposizione di tutti. Però me lo avete domandato davvero in molti quindi eccomi qui.

Nell’autunno del 2021 sono stata contattata da Paolo Chiarini, della Proloco “Città di Montichiari”. Sua intenzione, per il 25esimo dell’associazione, era di far dono alla città di un’opera d’arte urbana di mia mano. Io gli ho detto che preferivo non farmi carico di un’opera istituzionale perché dopo esperienze simili preferivo tornare a qualcosa di più intimo, come le installazioni nei luoghi abbandonati, dove avevo totale libertà di soggetto e destinatari.

Secondo Paolo a Montichiari avrei avuto soggetto libero lavorando sui temi a me cari perché era intenzionato a vedere un’opera che fosse libera da vincoli e totalmente mia, nulla di più. La musica sembrava interessante e allora si è deciso di proseguire.

Il Comune, dopo un primo muro che poi non era stato possibile recuperare poiché vincolato, gli aveva proposto di lavorare su una delle pareti esterne dell’Istituto don Milani, un muro di circa 200 m2.

Dopo un primo colloquio virtuale con gli interlocutori e la dirigente scolastica, la Prof.ssa Covri, mi è stato chiesto di coinvolgere in qualche modo gli studenti e l’unica strada possibile pareva quella della scelta del tema.

Ero un po’ perplessa (tengo molto a questo aspetto) e trattandosi di un numero altissimo di teste ho deciso di proporre una rosa di 6 tematiche a triade (più una cinquina) di mio interesse e far scegliere a loro quale fosse la più attuale, quella maggiormente sentita.

La preside ha quindi avuto l’idea di un sondaggio vero e proprio e dopo un paio di mesi ho avuto i risultati del sondaggio, in percentuale. Questi erano i temi:

- Cambiamenti climatici – riscaldamento globale – tutela biodiversità

- Inclusione – accoglienza – Intercultura

- Parità di genere – emancipazione – liberazione

- Diritto all’istruzione – dialogo educativo – relazioni

- Giustizia – pace – solidarietà – diritti umani – uguaglianza

- Disobbedienza civile – responsabilità – I care

- (proposta libera)

A febbraio la Provincia, proprietaria dell’immobile, aveva dato il permesso per la realizzazione dell’opera e quindi il 10 marzo, durante l’assemblea d’istituto, i ragazzi hanno votato. L’idea era quella di aprire brevi consultazioni a livello di ogni classe sulla scelta di una tematica e far votare in tempo reale la loro preferenza, frutto di una mediazione a livello di classe.

Il 24 febbraio l’offensiva militare delle Forze armate della Federazione Russa aveva invaso il territorio ucraino ed è facile pensare che la scelta sia caduta sul tema 5 per questo motivo, la guerra alle porte.

Dovevo quindi lavorare sulla tematica “Giustizia – pace – solidarietà – diritti umani – uguaglianza”. Mi sono maledetta da sola, ovviamente, parlare di speranza di pace in tempo di guerra, raccontare di diritti laddove vengono a mancare. Ero seriamente in crisi e la genesi del bozzetto è stata seriamente tribolata.

Ai primi di maggio però la mia idea era su carta e soprattutto avevo scritto la poetica, che riporto qui, perché è giusto che la leggiate a questo punto della storia, il senso è tutto lì.

Poi il racconto continua, promesso.

Poetica

Com’è difficile parlare di pace in tempo di guerra. In fondo, mi son detta, è costante tempo di guerra. Una reiterata e instancabile fiamma. Oggi qui, domani là, in un macabro rinfocolio.

La pace universale è assente dal mondo, ha sapore d’utopia.

Non per questo però possiamo smettere di coltivarla e proteggerla, di creare relazioni, di lottare contro la violenza e per la democrazia, la giustizia sociale e i diritti umani, condizioni necessarie affinché la pace possa vivere.

L’etimologia della parola pace rimanda alla radice sanscrita paç/pak/pag che si ritrova in pangere «fissare, pattuire, legare, saldare» e in pactum «patto».

A questo ho pensato creando la bozza dell’opera, un grande trittico che si sviluppa in stanze virtuali già delimitate dalle grondaie, un dipinto simbolico che evoca volutamente iconografie sacre.

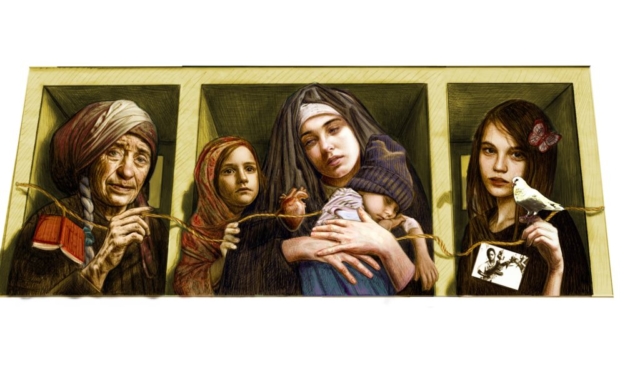

Cinque personaggi, i cui tratti somatici rivelano varie provenienze, che però non sono facilmente distinguibili perché vogliono rappresentare tutti. Tre figure al centro, stipate in uno spazio angusto e soffocante, e due ai lati, con piccole finestre dietro le spalle.

Separate da pareti senza aperture, queste persone possono comunicare solo attraverso una piccola corda (paç-as in sanscrito significa corda) che corre lungo tutta l’opera, passando dietro le grondaie.

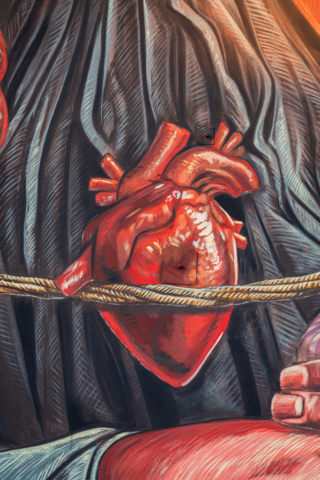

Una donna velata con gli occhi cerchiati dall’angoscia, delicata come una madonna manierista, stringe a sé un bambino dormiente ferito ad un braccio mentre una bimba le sbuca letteralmente da dietro la spalla, lo sguardo perso, proteggendosi con il corpo della madre e tenendo la piccola corda fra le dita. Al centro, un cuore umano sospeso è agganciato alla stessa cordicella e la sostiene (o ne è sostenuto? Quanto pesano i conflitti? Possiamo liberarci dallo strapotere dell’economia?).

A sinistra una donna anziana con turbante ci rivolge un silenzioso monito, reggendo la parte della corda alla quale è appeso un libro rovesciato. È un simbolo profetico che rappresenta non solo la cultura e il potere dell’educazione e del rispetto ma la letteratura stessa della pace e della nonviolenza.

A destra un’altra figura femminile, stavolta giovane e risoluta, tiene una colomba appoggiata alle dita e regge l’altro lembo della corda alla quale è appesa una fotografia che mostra un bambino soldato con un fucile in spalla.

Le figure laterali, moderne sibille, rivolgono lo sguardo all’osservatore (credo sia necessaria da parte di tutti l’assunzione di responsabilità) mentre i personaggi della stanza centrale dirigono gli occhi altrove.

Molte guerre giungono come echi sordi nel frastuono del quotidiano. Non è straniante provare empatia a distanza sentendosi comunque impotenti di fronte all’orrore?

Cosa possiamo fare di concreto? Continuo a domandarmelo.

🙂 Riprendo. Il 7 maggio mi muovo per un sopralluogo tecnico e vado al don Milani per incontrare proloco, dirigente e vice preside, sindaco e vice sindaco. Sono già decise le date di luglio per l’intervento e tutti hanno in mano bozza e spiegazione. Durante l’incontro il clima è un po’ teso e ci sono perplessità sulla bozza da parte della scuola. Mi vengono contestati alcuni simboli e il timore è che il risultato complessivo sia troppo ‘triste’, che l’opera possa risultare negativa e un ulteriore peso per gli studenti che escono da due anni di pandemia.

La cosa mi innervosisce un po’ e spiego per mezz’ora tutti i significati sottesi ad un pezzo come PAG e le possibilità che aprirebbe a livello didattico coi ragazzi, proponendo l’apertura di un sito a tema gestito dagli studenti e continuamente arricchito da testi e risultati di laboratori (sito raggiungibile da un QR code che avrei potuto dipingere sul libro). Non ho la minima intenzione di fare modifiche né di togliere il bambino col fucile, è la prima cosa che dico quando mi contattano, non lavoro su commissione. Ogni progetto è una sofferenza e chi mi conosce sa che è il motivo principale per il quale smetterò di lavorare in questo ambito.

L’incontro finisce, mi pare di aver parlato con sincerità ma mi sento un po’ delusa, l’opera si farà ma mi si raccomanda di usare dei colori brillanti per rendere il risultato più vivace (altra cosa che non capisco, un pezzo può essere tremendamente violento anche se ha colori brillanti, viceversa può essere sereno anche in bianco e nero), di raddrizzare il libro, di dare più forza alla colomba.

Comprendo le responsabilità di chi educa ma considero gli studenti delle superiori in grado di capire un pezzo così, sono anzi convinta che ciò che turba gli insegnanti non tocchi i ragazzi che probabilmente lo considereranno troppo edulcorato (se lo guarderanno, perché non è scontato, siamo tutti schiavi dello smartphone e ci perdiamo ogni giorno tante meraviglie distratti come siamo).

Esco dall’aula un po’ spoetizzata. Il colpo finale è la Provincia che chiede la bozza a colori (io le faccio sempre monocrome) con i codici RAL dei toni che userò, per l’impatto ambientale. Penso che di espressivo non resta più nulla ma lascio perdere, ho altro per la testa, devo produrre durc e duvri, il tempo corre.

Due mesi dopo, di ritorno dalla Danimarca, con meno di un’ora di sonno alle spalle (solito volo in ritardo di ore), arrivo a Montichiari. Scarico i materiali davanti alla palestra e alcuni giornalisti mi fanno delle domande circa il progetto, il soggetto, i destinatari. Nel frattempo arriva Fabio Fedele (cui ho chiesto una mano i primi 5 giorni, poi dovrà partire verso il nord Europa) e cominciamo a prendere le misure per la quadrettatura.

Dopo neanche mezz’ora mi arrivano notizie di articoli di quotidiani che parlano di una bocciatura del progetto da parte del don Milani poiché è stata resa nota una lettera della preside, firmata dal collegio docenti, che si dissocia totalmente perché la scuola ‘non è stata coinvolta’ e la mia opera ‘non è in linea con la mission dell’istituto’. È un po’ come ricevere un pugno in faccia, anzi, una pugnalata alle spalle.

Trovarsi a lavorare in casa di chi non ti vuole e scoprirlo quando sei già lì, con articoli che titolano ‘il don Milani boccia l’opera di Vera Bugatti’ e gente che passa urlando ‘questa è l’opera che non è piaciuta perché non c’entra con la scuola’.

Sono tentata di andare via, mi sento un po’ umiliata e soprattutto resto col dubbio di rientrare in una guerretta fra istituzioni mio malgrado (cosa che ritengo plausibile anche oggi). Scopro quindi che a Montichiari sono attive due proloco di diversa estrazione politica, cosa che ignoravo, e temendo che la mia opera possa essere strumentalizzata, sono decisamente nervosa.

La praticità di Fabio mi riporta alla quadrettatura e a razionalizzare. Sono convinta che il mio pezzo sintetizzi perfettamente il motto di don Milani I care (il contrario del me ne frego fascista) e mi decido a proseguire, lasciando parlare il pezzo, picta manent! mi piacerebbe dire.

Nel frattempo a scuola ci sono gli esami di maturità, quale insegnante svicola senza alzare lo sguardo, qualcuno invece viene a parlare, c’era anche chi mi incoraggia (ho compreso quindi che la posizione dei docenti non doveva essere per forza unanime). Gli articoli dei quotidiani seguono la vicenda calcando un po’ la mano, dandomi più notorietà di quanta ne abbia, stimolando la riflessione sul soggetto e dibattiti sui social. Della preside e vice nessuna traccia, mi è spiaciuto sinceramente. La Provincia poi, che aveva approvato il progetto a febbraio, esce con una frase davvero spiacevole relativa alla mia opera: “vedremo cosa farne a settembre”. Infine scopro, ma non posso esserne certa, che la scuola ha tentato in vari modi di bloccare il progetto in Provincia, insistendo sul fatto che la figura della madre in fuga con i figli ricorda iconografie sacre mentre la scuola deve restare laica. La questione non era emersa in colloquio e mi piace pensare che questa cosa non sia successa perché sarebbe un’argomentazione davvero povera. Sacra non è l’iconografia ma la tematica, e sacro non è sinonimo di religioso, questo mi sembrava chiaro.

In ogni caso, una situazione così surreale, per non dire kafkiana, non mi era mai capitata.

Una volta partito Fabio (che come sempre ha dato anima e corpo) mi ritrovo in piattaforma coi miei pensieri, valutando i casi, interrogandomi, svenendo per il gran caldo. Ritmi serrati, molta determinazione. Paolo sembra un po’ preoccupato per lo stress dovuto alla polemica, tiene molto al progetto e crede nel messaggio finale. Sono coccolata anche da Lara e Daniele e da vari amici venuti a trovarmi, ricevo tanti messaggi e chiamate, Angela (Franzoni) mi porta a cena perché vede che altrimenti non mangio, sto sempre lassù ed anche lei è un po’ preoccupata. La polemica aveva già mosso più di qualsiasi mia opera…

Alla fine sono come svuotata e parto in fretta per un progetto in Germania. Tornerò solo a metà luglio per l’inaugurazione e non ho tempo di pensare a nulla. Ormai l’opera è lì e ciò conta.

Il 17, dopo un volo cancellato e un complicato cambio di prenotazione (con l’aiuto della proloco), treni mezzi vari due voli quattro ore di ritardo e arrivo a Linate anziché a Orio.. vengo prelevata da Andrea in aeroporto e portata direttamente a Montichiari. Non capisco nulla, notte in bianco, pasti saltati ed escursione termica 14-39 gradi. Mi ritrovo lì con il microfono davanti ad una parete illuminata e rovente, non capisco nemmeno se c’è gente ma nel pubblico vedo la mia mamma ed è la miglior sorpresa.

Allora parlo, chi c’era si è già sorbito il monologo e non voglio ripetermi, forse lo posterò. Dopo aver introdotto la poetica dell’opera cito il filosofo coreano che stavo leggendo proprio realizzando il pezzo, Byung-chul Han (il libro è quello dedicato alla società senza dolore ma anche il saggio sulle non-cose è efficacissimo).

Con uno stile limpido e conciso parla dell’algofobia, ovvero della paura del dolore che contraddistingue la nostra società, intrufolandosi in ogni statuto psicologico e medico. Se ne rifugge in tutti i modi e ne nasce una società palliativa (e fortemente narcisistica) che rinuncia alla vita vera in cambio di una confortevole sopravvivenza.

Penso che proteggere le nuove generazioni dal mondo significa privarle della coscienza della responsabilità collettiva. Per questo non posso eliminare il tragico dalla mia opera, sarebbe un anestetico, potrebbe diventare un alibi. Vedere il ragazzo con il fucile e sapere chi vende e compra le armi è doveroso, essere consapevoli che durante le guerre la cultura altrui viene intenzionalmente cancellata è necessario, rendersi conto che se non creiamo relazioni non potremo mai reggere quella corda è fondamentale. Questo è PAG.

Grazie a chi mi ha ascoltata fino a qui.

Ecco il video del making of by Lorenzo Meid Eventi

(Now in English!)

A few months ago, I published the poetics of the PAG opera, created in Montichiari (BS) in July. I asked you for patience for the report of the project and I would have asked you more, as usual, because this week I would have to be in creative action on a new wall. Instead, I am technical knockout due to covid and after seven days I still have practically all the possible symptoms (friends know that my immune system is always on the spot … but I will recover).

So, I decided to tell you about Montichiari because there are still those who stop me and ask, but the controversy?

There is a lot to say, but perhaps little that is really worth remembering. At the end of July, I didn’t want to give interviews, I wanted to talk about the work, it seemed to me the best answer, and this answer remains there for everyone. But many have really asked me so here I am.

In the autumn of 2021, I was contacted by Paolo Chiarini, from the “Città di Montichiari” Association. His intention, for the 25th anniversary of the association, was to give the city a work of urban art by my hand. I told him that I preferred not to take on an institutional work because after similar experiences I preferred to return to something more intimate, such as installations in abandoned places, where I had total freedom of subject and recipients. According to Paolo in Montichiari I would have had a free subject working on the themes dear to me because he intended to see a work that was free from constraints and totally mine, nothing more. The music seemed interesting and it was decided to continue.

The Municipality, after a first wall that could not be recovered since it was bound, had proposed to him to work on one of the external walls of the Don Milani Institute, a wall of about 200 m2. After a first virtual interview with the interlocutors and the head teacher, Prof. Covri, I was asked to involve the students in some way and the only possible path seemed to be that of choosing the theme.

I was a bit perplexed (I care a lot about this aspect) and since we are dealing with a very high number of heads, I decided to propose a shortlist of 6 triad themes (plus about five) of my interest and let them choose which one was the most current, the one most felt. The principal then had the idea of a real survey and after a couple of months I had the results of the survey, as a percentage.

These were the themes: 1. Climate change – global warming – biodiversity protection 2. Inclusion – welcome – Interculture 3. Gender equality – emancipation – liberation 4. Right to education – educational dialogue – relationships 5. Justice – peace – solidarity – human rights – equality 6. Civil disobedience – responsibility – I care 7. (free proposal).

In February the Province, owner of the property, had given permission for the construction of the work and then on 10 March, during the institute assembly, the boys voted. The idea was to open short consultations at the level of each class on the choice of a topic and have their preference voted in real time, the result of mediation at the class level.

On February 24, the military offensive of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation had invaded the Ukrainian territory and it is easy to think that the choice fell on theme 5 for this reason, the war at the gates.

Well, I had to work on the theme “Justice – peace – solidarity – human rights – equality”. I cursed myself, of course, to talk about the hope of peace in wartime, to talk about rights where they are lacking. I was seriously in crisis and the genesis of the sketch was seriously troubled.

In early May, however, my idea was on paper and above all I had written the poetics, which I report here, because it is right that you read it at this point in the story, the meaning is all there. Then the story continues, promised.

Meaning of the artwork:

How difficult it is to speak of peace in times of war.

After all, I said to myself, it is constant wartime. A repeated and tireless flame. Today here, tomorrow there, in a macabre resuscitation.

Universal peace is absent from the world, it has the flavor of utopia. However, this does not mean that we can stop cultivating and protecting it, creating relationships, fighting against violence and for democracy, social justice and human rights, necessary conditions for peace to live.

The etymology of the word peace refers to the Sanskrit root paç / pak / pag which is found in pangere “to fix, agree, bind, weld” and in pactum “pact”.

I thought of this by creating the draft of the work, a large triptych that develops in virtual rooms already delimited by the gutters, a symbolic painting that deliberately evokes sacred iconographies.

Five characters, whose somatic features reveal various origins, which however are not easily distinguishable because they want to represent everyone. Three figures in the center, crammed into a narrow and suffocating space, and two on either side, with small windows behind them. Separated by walls without openings, these people can communicate only through a small rope (paç-as in Sanskrit means rope) that runs along the entire work, passing behind the eaves.

A veiled woman with eyes circled in anguish, as delicate as a mannerist madonna, hugs a sleeping child wounded in the arm while a child literally emerges from behind her shoulder, gazing lost, protecting herself with her mother’s body and holding the little rope between the fingers. In the center, a suspended human heart is hooked to the same cord and supports it (or is it supported? How heavy are the conflicts? Can we free ourselves from the excessive power of the economy?).

On the left, an elderly woman wearing a turban gives us a silent warning, holding the part of the rope to which an overturned book hang. It is a prophetic symbol that represents not only the culture and power of education and respect but the literature of peace and nonviolence itself.

On the right, another female figure, this time young and resolute, holds a dove resting on her fingers and holds the other end of the rope to which hangs a photograph showing a child soldier with a rifle on his shoulder. The lateral figures, modern sibyls, turn their gaze to the observer (I think everyone must assume responsibility) while the characters in the central room direct their eyes elsewhere.

Many wars come as dull echoes in the din of everyday life. Isn’t it alienating to feel empathy from a distance while still feeling powerless in the face of horror? What can we do concretely? I keep wondering.

On 7 May I move for a technical inspection and I go to Don Milani to meet proloco, manager and vice president, mayor and deputy mayor. The dates of July for the intervention have already been decided and everyone has a draft and an explanation in their hands.

During the meeting, the atmosphere is a bit tense and there are doubts about the draft by the school. Some symbols are disputed and the fear is that the overall result is too ‘sad’, that the work may be negative and an additional burden for students who come out of two years of pandemic. This makes me nervous a bit and I explain for half an hour all the meanings underlying a piece like PAG and the possibilities it would open at the educational level with the students, proposing the opening of a themed site managed by students and continuously enriched by texts. and laboratory results (site reachable by a QR code that I could have painted on the book).

I have no intention of making changes or removing the baby with the gun, that’s the first thing I say when they contact me, I don’t work on commission. Every project is a pain and those who know me know that it is the main reason why I will stop working in this area.

The meeting ends, I think I have spoken sincerely but I feel a bit disappointed, the work will be done but it is recommended that I use bright colors to make the result more lively (something else I don’t understand, a piece can be tremendously violent even if it has bright colors, vice versa it can be serene even in black and white), to straighten the book, to give more strength to the dove.

I understand the responsibilities of those who educate but I consider high school students able to understand a piece like this, I am indeed convinced that what disturbs the teachers does not affect the children who will probably consider it too sweetened (if they will look at it, because it is not obvious, we are all slaves of the smartphone and we lose every day many wonders distracted as we are).

I leave the classroom a little spoiled. The final blow is the Province asking for the color draft (I always make them monochrome) with the RAL codes of the tones that I will use, for the environmental impact. I think that there is nothing left of expressiveness but I let it go, I have other things on my mind, I have to produce durc and duvri, time is running out.

Two months later, returning from Denmark, with less than an hour of sleep behind me (usually a flight delayed by hours), I arrive in Montichiari. I download the materials in front of the gym and some journalists ask me questions about the project, the subject, the recipients. In the meantime, Fabio Fedele arrives (from whom I asked for a hand the first 5 days, then he will have to leave for northern Europe) and we begin to take the measurements for the grid.

After less than half an hour I get news of newspaper articles that speak of a rejection of the project by Don Milani because a letter from the headmaster was made known, signed by the teachers’ college, which totally dissociates itself because the school has not been involved ‘and my work’ is not in line with the mission of the institute ‘. It’s a bit like getting a punch in the face, or rather, a stab in the back. Finding yourself working in the home of those who don’t want you and finding out when you’re already there, with articles titled ‘Don Milani rejects Vera Bugatti’s work’ and people who pass by screaming ‘this is the work that is not liked because it has to do with school ‘.

I am tempted to leave, I feel a little humiliated and above all I remain with the doubt of returning to a war between institutions in spite of myself (which I think is plausible even today). I therefore discover that in Montichiari there are two prolocos of different political origins, which I did not know, and fearing that my work could be exploited, I am definitely nervous. Fabio’s practicality brings me back to grid lines and to rationalize.

I am convinced that my piece perfectly summarizes Don Milani’s motto I care (the opposite of I don’t care fascist) and I decide to continue, letting the piece speak, picta manent! I would like to say. In the meantime, at school there are the final exams, which teacher slips away without looking up, someone instead comes to talk, there were also those who encourage me (I therefore understood that the position of the teachers did not necessarily have to be unanimous).

The newspaper articles follow the story by treading a little hand, giving me more notoriety than I have, stimulating reflection on the subject and debates on social media. No trace of the principal and deputy, I was sincerely sorry. The Province then, which had approved the project in February, comes up with a really unpleasant sentence relating to my work: “we’ll see what to do with it in September”.

Finally, I discover, but I cannot be sure, that the school has tried in various ways to block the project in the Province, insisting that the figure of the fleeing mother with her children recalls sacred iconographies while the school must remain secular. The issue did not emerge in the interview and I like to think that this did not happen because it would be a really poor argument. Sacred is not the iconography but the theme, and sacred is not synonymous with religious, this seemed clear to me.

Such a surreal situation had never happened to me.

Once Fabio left (who as always has given body and soul) I find myself on the platform with my thoughts, evaluating the cases, questioning myself, fainting from the heat. Fast pace, a lot of determination. Paolo seems a bit worried about the stress caused by the controversy, he is very keen on the project and believes in the final message. I am also pampered by Lara and Daniele and by various friends who have come to visit me, I receive many messages and calls, Angela (Franzoni) takes me to dinner because she sees that otherwise I do not eat, I am always up there and she too is a little worried. The controversy had already moved more than any of my works!

In the end, I feel drained and I leave quickly for a project in Germany. I will only be back in mid-July for the inauguration and I don’t have time to think about anything. Now the work is there and that matters.

On the 17th, after a canceled flight and a complicated change of booking (with the help of the proloco), trains means various two flights four hours late and arrival at Linate instead of Orio … I am picked up by Andrea at the airport and taken directly to Montichiari. I don’t understand anything, sleepless night, skipped meals and temperature range 14-39 degrees. I find myself there with the microphone in front of an illuminated and hot wall, I don’t even understand if there are people but in the audience, I see my mom and it’s the best surprise.

Then I talk, whoever was there has already endured the monologue and I don’t want to repeat myself, maybe I’ll post it.

After introducing the poetics of the work, I quote the Korean philosopher I was reading while making the piece, Byung-chul Han (the book is the one dedicated to society without pain but also the essay on non-things is very effective). With a clear and concise style, he speaks of algophobia, or the fear of pain that distinguishes our society, sneaking into every psychological and medical status. He shuns it in every way and a palliative (and strongly narcissistic) society is born that renounces real life in exchange for a comfortable survival.

I think that protecting the new generations from the world means depriving them of the consciousness of collective responsibility.

This is why I cannot eliminate the tragic from my work, it would be an anesthetic, it could become an alibi. Seeing the boy with the rifle and knowing who sells and buys weapons is a must, being aware that during wars the culture of others is intentionally canceled is necessary, realizing that if we don’t create relationships, we will never be able to hold that rope is essential. This is PAG. Thanks to those who have listened to me up to here.